During some projects, commissioning providers may have limited chances to have our recommendations heard. I have found that if your recommendation includes challenging the Big Mistake1 often seen with a demand-controlled ventilation (DCV) sequence for air-handing units (AHUs), you better be prepared for some unexpected arguments from the defender of that sequence. Having read last month’s column may not be enough. It's best that you mentally prepare yourself through visualization for this potentially very awkward conversation.

The Big Mistake recap

If you haven’t read last month’s column, I highly recommend you do so before proceeding. The gist of the article details the Big Mistake when it comes to DCV. Far too often, the range of values used for the minimum outdoor airflow set point for an AHU are not appropriate. The correct approach would be to reset the minimum outdoor airflow set point downwards from an upper limit, which corresponds to the design minimum airflow rate that satisfies ventilation requirements during fully occupied periods (see Figure 1). The Big Mistake is that, often, the set point range specified and/or programmed includes resetting the minimum outdoor airflow rate from the design minimum as the lower limit up to 100% outdoor air as an upper limit. The consequences of that mistake are detailed in the previous column. This month’s column is intended to prepare commissioning providers to appropriately articulate to the passionate defenders of this flawed sequence why the Big Mistake is even a mistake at all.

The conversation

The following is a fictional conversation between me and a design engineer that borders on satire. However, I can assure you it is based on a collection of actual conversations had with various defenders of the Big Mistake (design engineers, temperature controls contractors, and building operators). I have heard most of the arguments presented by the fictional design engineer below, many times in my career.

Me: I am concerned your DCV sequence is incorrect. We should not increase the minimum airflow setpoint above the design minimum.

Design Engineer: Why would we limit the ventilation provided to occupants if CO2 concentrations are getting unacceptably high? Are you recommending that we hold the system back from providing the fresh air the people clearly need?

Me, thinking to myself: Well, that escalated quickly. Is he accusing me of trying to harm the occupants?

Me: I understand your design calls for a certain minimum outdoor airflow needed when the building is at maximum occupancy. Shouldn’t that design minimum value you determined be sufficient to meet the ventilation requirements of the occupants?

Design Engineer: Correct — then CO2 concentrations should not exceed set point. So, this should be a nonissue.

Me: Unless the CO2 sensor falls out of calibration, which they often do.

Design Engineer: Facility operations will need to include sensor calibration in the preventive maintenance program.

Me: Has this information been presented to the facility operations team? Does the client currently use CO2-based DCV elsewhere? What do their current preventive maintenance tasks on such sensors look like?

Design Engineer: (Crickets).

Me: What is the proper CO2 set point to be used for the occupancy classification?

Design Engineer: 1,000 ppm, but we made that an adjustable setpoint.

Me, thinking to myself: Clearly not much thought was put into this.

Me: So, you are willing to let the system bring in higher quantities of outdoor air than it was designed to handle during extreme hot and cold days in order to ensure CO2 concentrations (measured from a sensor of questionable accuracy) stays below some generic set point, which may not be appropriate for the spaces served for this particular system?

Design Engineer: Listen, I don’t want to restrict the economizer from bringing in more outdoor air to save energy.

Me: This has nothing to do with economizing. Did you even read my October column in Engineered Systems magazine? If not, here is a laminated figure from that article.

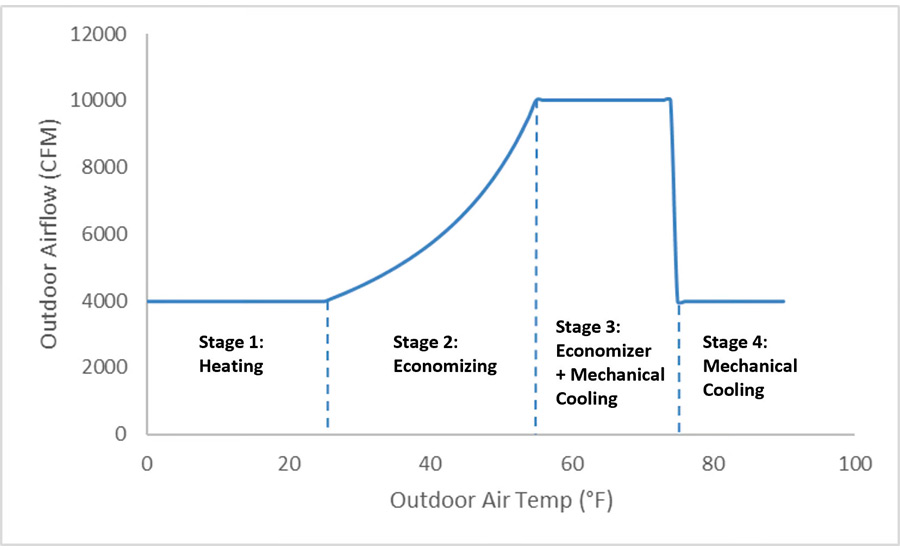

Though the minimum outdoor airflow and economizer control strategies are related, they are distinctly different aspects of an AHU’s control strategy. DCV is intended to save energy in Stages 1 and 4 (see Figure 2) during partial occupancy, when the AHU is controlling for a minimum amount of outdoor air. It will not limit the economizer, which is operational during Stages 2 and 3. Actually, it will only allow for more hours of economizer operation, as a lower minimum outdoor airflow requirement will widen the range of outdoor air temperatures, which Stage 2 will operate between. Economizers are intended to save energy in Stages 2 and 3, DCV is intended to save energy in Stages 1 and 4. The strategies compliment each other, they don’t fight against each other.

Design Engineer: (Crickets).

Me, thinking to myself: Maybe I should try this from another angle.

Me: Exceeding the design minimum outdoor airflow rate will waste energy and potentially put the system at risk of overextending the heating or cooling coils. Overextended heating and cooling coils will result in loss of humidity and temperature control, freeze stat trips, or maybe even frozen coils.

Design Engineer: (Crickets).

Me: Listen, I do believe this sequence is fundamentally flawed. However, if this sequence is really desired, will the coils be upsized to handle 100% outdoor air on design heating and cooling days? That does not appear to be the case in your current design.

Design Engineer: That would be a significant cost impact to upsize the systems to handle 100% outdoor airflow. We can ask the contractor to price up this and other recommendations that are generated during your commissioning process. We can then provide that pricing to the client for consideration.

Me, thinking to myself: How did this get spun into being my idea? Is this what it feels like when someone is gaslighting you?

Me: I am not advocating for the increased amount of outdoor air that would come from this control sequence. I am also not advocating for upsizing mechanical systems to accommodate this flawed strategy. Are you not at all concerned with overextending a heating coil with this strategy, given the coil was not scheduled or selected for 100% outdoor air on a very cold day? Freezing a coil is a very bad day for everyone involved.

Design Engineer: There is usually a safety control to back off on the outdoor airflow if the heating coil leaving temperature gets too low in the AHU.

Me: Are you referencing the specified freeze stat? Because that won’t just reduce outdoor airflow, that will disable the entire AHU.

Design Engineer: No. I'm referencing a sequence where the heating coil leaving temperature is measured, and if it falls below 40°F, then the outdoor air damper would modulate to close more. All this would occur well before the freeze stat ever tripped!

Me: OK, I am familiar with that strategy, but this is not in your specified sequence of operation.

Design Engineer: But they usually program it.

Me: And, if they don’t?

Design Engineer: The facilities team has a good relationship with the temperature controls contractor. I would bet such a sequence to limit outdoor air when heating coil leaving temperature gets too low is part of their facility standards.

Me. Wait, they have a facility standard for control sequences? I was not tracking that. Shouldn’t your specified sequence of operation incorporate any such standards?

Design Engineer: Listen, I have to run to another meeting, I didn’t think this conversation would take so long.

Me. Trust me, neither did I.

Conclusion

There are far more pitfalls that hold back this sequence than discussed in this and last month’s column. And, while I'm not some outspoken advocate on DCV in AHUs, I am, however, energy, budget, and time conscience. And, more than anything, I believe if you are going to do something, you better do it right. DCV in AHUs, if applied correctly, can save energy. Unfortunately, I have found the Big Mistake occurs more often than it doesn’t. Convincing defenders of the Big Mistake that they are thinking about the DCV wrong has, at times, been a difficult challenge for me. Hopefully, the last two columns on DCV can assist readers in leading their commissioning teams to better outcomes in addressing the Big Mistake head on.

References:

1Ryan, M. 2023. “Setting the Record Straight on DCV.” Engineered Systems Magazine (October).

2ASHRAE Guideline 36-2021, High-Performance Sequences of Operation for HVAC Systems.

3 Lawrence, T. 2008. “Selecting CO2 Criteria for Outdoor Air Monitoring.” ASHRAE Journal (December)