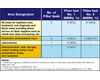

Figure

1. Table 2.1-3, “Filter Efficiencies For Central Ventilation And

Air Conditioning Systems In General Hospitals.”

In almost any aspect of health care, standards and/or regulations can border on the overwhelming. Air filtration is no different, yet as in other aspects of health care, proper performance is critical for safety as well as licensure. Keep up with classifications for filtration efficiencies, three patient segregation categories pertinent to filtration, and the latest on various professional guidance.

On February 14, 1947, filtration efficiencies for hospital and health care facilities originally appeared as general standards in the Federal Register as part of the implementing regulations for the Hill-Burton program.

The 1974 edition marked the first request for public input and comment. The document was re-titled “Minimum Requirements of Construction and Equipment for Hospital and Medical Facilities” to emphasize that the requirements were minimum, rather than recommendations of ideal standards.

In 1984, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) removed from regulation the requirements relating to minimum standards of construction, renovation, and equipment of hospitals and other medical facilities, as cited in the “Minimum Requirements Department Health, Education & Welfare” (DHEW), Publication No. [HRA] 81-14500. To reflect the non-regulatory status, the title was changed to “Guidelines for Construction and Equipment of Hospital & Medical Facilities.”

Also in 1984, DHHS asked the American Institute of Architects Committee in Architecture for Health (AIA/CAH) to form an advisory group. The AIA finally reached an agreement with the DHHS to publish the 1987 edition of the guidelines.

Subsequently, the AIA published and distributed the 1992-93 edition of the guidelines. The Steering Committee from the 1992-93 cycle requested and received federal funding from the DHHS for another cycle.

To better reflect the content, the title of the document was changed to “Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospital & Healthcare Facilities.” It was during this revision that the AIA/CAH became the AIA Academy of Architecture for Health (AIA/AAH). The Health Guidelines Revision Committee (HGRC) reviewed the 1996-97 edition line by line to ascertain areas that needed to be addressed, including infection control, safety, and environment of care.

In 1998, in an effort to create a formal procedure and process as well as to keep the document current, the Facilities Guidelines Institute (FGI) was formed. The main objective of the FGI is to see that the guidelines were reviewed and revised on a regular cycle via a consensus process by a multidisciplinary group of experts from federal, state, and private sectors.

Currently

The 2006 edition of the guidelines has reviewed 797 proposals for change. The newest edition also received major funding from DHHS/Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, ASHE, and the NIH and the AIA again provided staff and technical support for the 2006 edition as well. At the beginning of this revision cycle, a notice that the document was being revised was publicized to interested parties along with a request that they make proposals for change. The HGRC received and gave careful consideration to 1,156 comments on proposed changes.For the first time, the Internet was used exclusively to distribute the document and to receive proposals and comments. The 2006 edition of the guidelines was approved by the FGI and turned over to the AIA for publication and distribution. In addition, for the first time, the current 2006 edition of the guidelines has included a searchable CD-ROM version of the book.

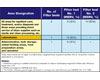

Figure

2. Table 3.1-1, “Filter Efficiencies for Central Ventilation and

Air Conditioning Systems in Out Patient Facilities.”

When possible, the guideline’s standards are performance-oriented for results. Prescriptive measurements, when given, have been carefully considered relative to generally recognized standards. Today, health care providers reference the guidelines when planning new or renovated health facility construction. Authorities in 42 states, the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), and several federal agencies also use the guidelines as a reference code or standard when reviewing, approving, and financing plans and when surveying, licensing, certifying, or accrediting completed facilities. The guidelines are also used by state licensure agencies as a model for writing their codes, and for this reason, regulatory language has been retained.

Filtration Efficiencies

Other health care facilities:- Hospice

- Assisted living

- Adult day health care

- Filter frames shall be durable and proportioned to provide an airtight fit with enclosing ductwork.

- All joints between filter segments and enclosing ductwork shall have gaskets or seals to provide a seal against air leakage.

- A manometer shall be installed across each filter bed having a required efficiency higher than 75%, including hoods requiring HEPA filters.

- Where two filter beds are required, filter bed No. 1 shall be located upstream of air conditioning equipment, and filter bed No. 2 shall be located downstream of any fans or blowers.

- If humidifiers are installed, they shall be located at least 15 ft upstream from final filters.

- All other health care facility filter efficiency requirements shall use the Table 2.1-1 standard.

Significant changes have been incorporated into these guidelines with regard to infection control. To every extent possible, these changes conform to the most current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) “Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis in Healthcare Facilities” and “Guidelines for Prevention of Nosocomical Pneumonia, 1994,” published by the CDC in the American Journal of Infection Control (22:247-292).

Three patient segregation categories have been identified as follows:

Airborne infection isolation room. Airbone infection isolation rooms shall operate under negative pressure with a minimum of 12 ach. In airborne infection rooms, the air may be recirculated if HEPA filters are used. In rooms with reversible airflow provision for the purpose of switching between protective environment and airborne infection isolation, these functions are not acceptable. Pressure differential shall be 0.01 in. w.g.

Protective environment room.Protective environment rooms shall operate under a positive pressure with a minimum of 12 ach and have HEPA filters at 99.97% efficiency on 0.3 micrometer, (µm) size particles in the supply airstream. Pressure differential shall be 0.01 in. w.g.

Immune suppressed host on airborne infection isolation. Anterooms are recommended for patients who are immune suppressed and potential transmitters of airborne infection. Rooms with dual-purpose or switch-reversible airflow mechanisms between positive and negative are no longer acceptable.

Summary

The 2006 edition of “Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospital and Healthcare Facilities” offers those responsible for health care design and construction, a detailed, up-to-date document. This new edition also covers equipment requirements for hospice care, adult day care, and assisted living facilities. There are several other important revisions and additions in the guidelines that those professionals serving the health care industry should review.ESReferences

- The American Institute of Architects Academy of Architecture for Health.

- The Facilities Guidelines Institute with assistance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 52.1-1992

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 52.1-1999

Notes:

1. Additional roughing or prefilters should be considered to reduce maintenance required for main filters.

2. The MERV Numbers are based on ANSI/ASHRAE Std. 52.2.

3. The filtration efficiency ratings are based on average dust spot efficiency per ANSI/ASHRAE Std. 52.1.