Initially envisioned as a building-wide network protocol, BACnet (ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 135-1995, "Building Automation Control Network") is now being used to join buildings together on campus-wide internetworks. And there is increasing demand to interconnect BACnet systems across cities, regions, countries, and even continents.

In nearly all cases, the desire is to use an existing Internet Protocol (IP), wide-area network (WAN) already spanning the area to join the BACnet systems. However, BACnet devices and IP devices speak different protocols, different languages; one cannot simply plug them into the same network and expect them to work.

Special devices are required in order for BACnet messages to be transported across IP networks to BACnet devices in distant locations. These devices, described in the standard, are already in use.

Last year, for instance, BACnet networks at the Phillip Burton Federal Building (San Francisco), Cornell University (Ithaca, NY), and the National Institute of Science and Technology (Gaithersburg, MD) were all joined together over the Internet, in a public demonstration of a very wide area BACnet system indeed.

The following is a look at the devices and methods by which BACnet networks are interconnected over IP WANs.

Internetworking And Routers

It is often necessary to set up multiple networks to communicate with each other. This may be required because different network types with different characteristics are being used.For example, Ethernet, which is frequently used in building automation systems (bas), works well as a building-wide network, but it cannot span a continent. Other network technologies must be used for such long distances. Thus, multiple networks must be used if buildings in distant locations are to be joined in a single system.

For multiple networks to communicate, there must be a common language or protocol used by the devices on those networks. For BACnet devices, the protocol is BACnet.1 For IP networks, of course, it is the underlying protocol used by the Internet itself, as well as by many private networks.

The protocol defines the format of the message packets exchanged between devices. It also defines the format of the message frame, the surrounding envelope that determines what destination address should be used, and what protocol the frame is using.

Some protocols, such as BACnet, define the entire frame and packet together. Other protocols, such as IP, can state within the frame that a different protocol is to be used to decode the packet within.

When multiple networks using the same protocol for their packets are joined, the result is called an internetwork.2 (It is also called an "internet," but that term is too easily confused with the Internet, the best-known internetwork.) Internetworks can also be created with multiple networks using different protocols if a device called a protocol converter, also known as a gateway, is used to translate the messages going back and forth.

The devices that join the networks of an internetwork are known as routers. Unlike most devices that connect to a single network, routers connect to two or more networks for the purpose of forwarding messages sent by a device on one network and destined for a device on another network.

In complex internetworks, a message may have to be forwarded through several routers and across several networks before reaching its destination.

A router must be able to understand the frame's protocol in order to determine whether or not a message is destined for another network. If the message is destined for a device on the same network, the router must not pass it on; doing so would flood the rest of the internetwork with extraneous messages. Thus, BACnet routers must understand BACnet frames and IP routers must understand IP frames.

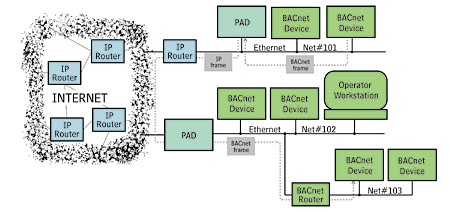

BACnet internetworks that are connected only by routers that understand BACnet frames are defined here as directly connected internetworks. (In Figure 1, networks 102 and 103, but not 101, comprise a directly connected internetwork.) This distinguishes them from the super-internetworks, serving to join multiple directly connected internetworks, which can be created by devices that allow BACnet packets to be carried within IP frames.

The Problem And Its Solutions

The problem one encounters when trying to connect the component BACnet networks (or directly connected BACnet internetworks) of a wide-area BACnet internetwork together over an IP wide-area network, is that IP routers do not understand BACnet frames.If an IP router has a connection to a BACnet network and receives a BACnet frame that needs to be delivered to another network, it will do...nothing.3

The problem is solved with special kinds of BACnet devices that also understand the IP protocol. Such a device is able to take a BACnet message and enclose it within an IP frame that an IP router can read and deliver across an IP internetwork.

At the destination, another such BACnet device extracts the BACnet message from the IP frame, reads it, and forwards it if necessary.

Annex H.3 of the original BACnet standard describes this technique known as "tunneling," by which devices called B/IP PADs (BACnet/Internet-Protocol Packet-Assemblers-Disassemblers), also known as Annex H.3 devices, act like routers to transport BACnet messages across IP internetworks.

A recent addition to the BACnet standard, Annex J-BACnet/IP, describes a flexible extension of the original concept. It even includes descriptions of BACnet/IP devices that always enclose their BACnet messages within IP frames.

BACNET/IP Pads

To connect BACnet networks over IP networks, a special kind of router called a BACnet/IP PAD (BACnet/Internet-Protocol Packet-Assembler-Disassembler) is placed on every BACnet network (or directly connected internetwork) that is to be connected over an IP network to another BACnet network. The PAD need not be a physically distinct device; it can be part of a device that performs other operations, such as a building controller.The PAD acts like a BACnet router. When it receives a BACnet message destined for a distant BACnet network, a network reachable only through an IP internetwork, it wraps the message inside an IP frame, gives the frame the destination IP address of the corresponding PAD on the destination BACnet network, and sends the frame on its way over the IP network.

The receiving PAD removes the BACnet message from its IP frame and transmits the message to the destination device on the local LAN, just as if it had come from a BACnet router.

The BACnet devices originating and receiving the messages are unaware of the special operations used to deliver the messages. They communicate with the PADs as if the PADs were ordinary BACnet routers connecting BACnet networks.

Two configurations of PADs exist, as shown in Figure 1. The first has a single physical network connection, or port, typically to an Ethernet network, through which both BACnet and IP frames are transmitted and received.

It requires an IP router to be connected to this network in order to have its IP frames delivered to the distant PAD. (The PAD may also have other BACnet-only ports.)

The second PAD configuration has different ports for BACnet and IP frames. The IP port may thus be directly on the IP internetwork connecting the BACnet networks. Typically, the PAD appears to the IP internetwork as a device communicating using IP, not as an IP router.

Virtual Networks

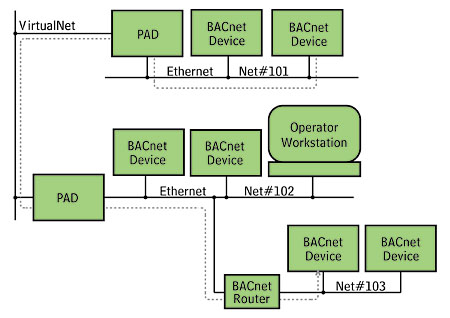

Depending upon the implementation, a set of intercommunicating PADs can look to devices on the BACnet networks like a single physical router with a port on each of the BACnet networks to which it is connected.The IP routers and networks that participate in the communications are completely invisible to the BACnet devices.

In a different implementation, the PAD devices will instead appear to the BACnet networks as BACnet routers directly connected by a single network. This network is called a "virtual network" because it will usually be an internetwork composed of multiple IP networks instead of a single physical network.

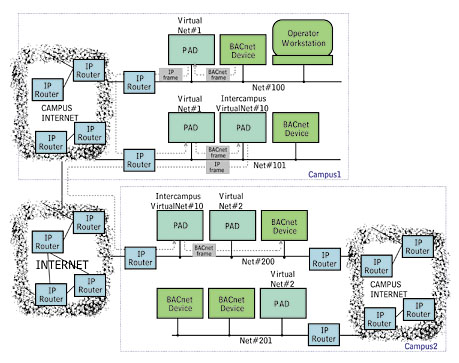

Figure 1 shows the physical implementation of such an internetwork. Figure 2 shows the internetwork, including the virtual network, as it appears to the BACnet devices.

One significant difference between PADs and other BACnet routers is the way global (internetwork-wide) broadcasts are handled. Other routers rebroadcast the message on all networks other than the one the message came from, but a PAD sends a separate IP frame to each of its peer PADs.

This avoids the use of broadcast IP frames, a practice frowned upon by many network administrators. It also requires that the PAD keep a table of its peers' IP addresses.

Careful attention must be paid to certain BACnet rules when constructing a wide-area BACnet internetwork. Parameters that are required to be unique across a BACnet internetwork (such as every device object's Object Identifier, Object Name properties, and network numbers) must remain unique when already-operating networks are subsequently interconnected via a wide-area IP network. Failure to follow this rule is a common source of trouble.

One of the most critical BACnet rules to be obeyed is that there must be only one path across the internetwork for BACnet frames to traverse between any two devices. This means there cannot be more than one PAD device connected to a directly connected BACnet internetwork (unless each PAD is on a different virtual network, as explained later).

This path restriction does not apply to the IP frames transferred between PADs. There may, for example, be more than one IP router connecting the BACnet network to the IP Internet and basic PAD devices may take advantage of this fact, automatically rerouting their IP frames through the secondary IP router if the primary IP router fails.

Configuring A Pad

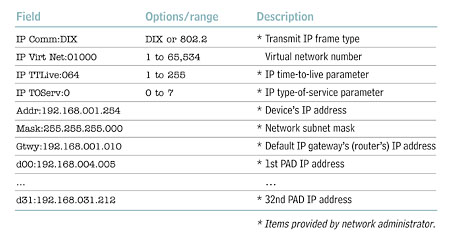

Configuring a PAD device seems complex because of the number of IP parameters that need to be entered, but in fact, nearly all the parameters should be provided by a network administrator responsible for the IP internetwork. The only non-IP parameter is the BACnet network number to be assigned to the virtual network. Depending upon their implementation, some PADs might not have this parameter.A representative PAD device setup menu is shown in Figure 3. The device menu in Figure 3 shows that PAD devices have fixed (assigned) IP addresses, unlike many devices that can be assigned an IP address automatically upon each startup by a server on the IP network.

Although this makes for more work for the network administrators, it is necessary; without fixed addresses, there is currently no means for the B/IP PAD devices to locate each other without broadcasting queries.

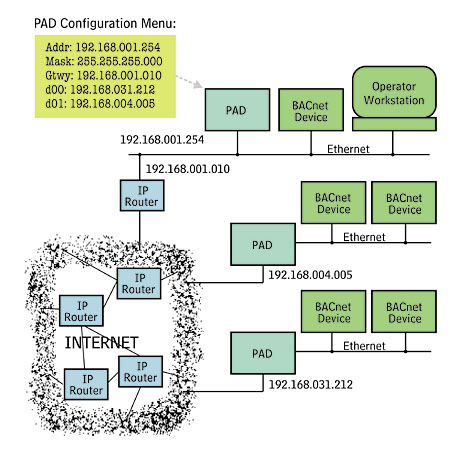

Figure 4 shows the relationship between a PAD's IP address parameters and the configuration of an actual network. The IP addresses are shown in the common "dotted quad" form: four decimal numbers, each in the range from 0 to 255, separated by periods. These numbers represent the four bytes of the actual IP address.

Multiple Virtual Networks

PAD devices will have a limit to the number of other PADs with which they can communicate, due to restrictions on memory and the communications bandwidth. If the PADs will talk to, say at most, 31 other PADS, only 32 directly connected BACnet internetworks can be joined by a single virtual network.This does not place a limit on the total number of BACnet networks that may be joined over IP internets, however. Multiple virtual nets may be constructed and connected to create a "super" virtual internetwork.

Two multiple virtual networks are connected when a PAD device from each of the two virtual networks is placed on the same BACnet network. In Figure 5, for example, virtual network #1 is joined to virtual network #10 by the two PADs on (physical) network #101.

Sometimes it may be desirable to construct multiple virtual networks where the PAD limitations have not been reached. An example is a wide-area BACnet internetwork joining all the buildings of a number of distant campuses. Each building has its own BACnet network, and has access to its campus-wide IP internetwork; each campus IP internetwork is part of a larger IP internetwork joining the campuses. Each campus can be serviced by a single virtual network, but there are far too many buildings for a single virtual network to cover all buildings in all campuses.

In this scenario, it makes sense to construct a separate virtual network within each of the campuses, and a third virtual network joining the campuses. Figure 5 illustrates this implementation in a two-campus internetwork. Each campus has its own IP internetwork with its own virtual network, #1 and #2 (presumably, there are many more networks in each campus than are illustrated). The two campuses are joined by a third virtual network, #10.

As with the single virtual network, BACnet rules must be observed throughout the entire BACnet internetwork. Only one PAD device from any particular virtual network may be connected to a BACnet directly connected internetwork.

Virtual networks must not be connected so that more than one path through BACnet physical or virtual networks exists between any two BACnet devices. Any failure to observe these rules will be immediately evident as internetwork traffic volumes skyrocket, possibly shutting down the networks, and definitely making some network administrator very unhappy.

FOOTNOTES

1 See "The Language of BACnet," Engineered Systems, July 1996.

2 See "Internetworking with BACnet," Engineered Systems, January 1997.

3Some IP routers can be configured to pass through any message carrying the code identifying it as a BACnet message, but this can result in the IP internet-work being flooded with BACnet messages.

ES